A beginner’s guide to the DNS (Domain Name System) and what DNS records are. With answers to the commonly asked domain and DNS questions.

What Are Domain Names?

Let’s start at the very beginning.

Before understanding DNS, you need to understand what domain names are.

Domain names are the human-understandable address to a service on the internet.

For example:

google.com, youtube.com, abc.net.au, WilBrown.au (shameless plug of my website!)

What Is DNS?

DNS stands for Doman Name System, which translates human-understandable domain names to machine-understandable Internet Protocol addresses (IP addresses).

For example:

IP v4 address: example.com → 172.75.127.3

IP v6 address: example.com → 2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

You may stand a chance of remembering a few IP4 addresses, but there’s no way to remember IP6 addresses unless you have an eidetic memory.

Computers could happily talk to each other using IP addresses, so DNS is for humans.

How Does DNS Work?

We can simplify how DNS works by looking at four critical points in the system. These are:

- Your computer

- Your ISP’s (internet service provider) recursive name server

- Root name servers

- Authoritative name servers

Your Computer

Your computer is, of course, connected to the internet in your house or office.

Your ISP’s Recursive Name Server

A recursive name server is the first stop in a DNS query, usually a server used by your Internet Service Provider (ISP).

The recursive resolver acts as a middleman between a client (web browser or your local computer) and a DNS nameserver.

After receiving a DNS query from a web client, the recursive name server will either respond with cached data, or send a request to a root nameserver, followed by another request to a TLD (Top Level Domain) nameserver, and then one last request to an authoritative nameserver.

After receiving a response from the authoritative nameserver containing the requested IP address, the recursive resolver sends a response to the client.

Your domain name’s name servers are likely to be your website ISP’s servers, but they could also belong to a CDN (Content Delivery Network) service such as Cloudflare.

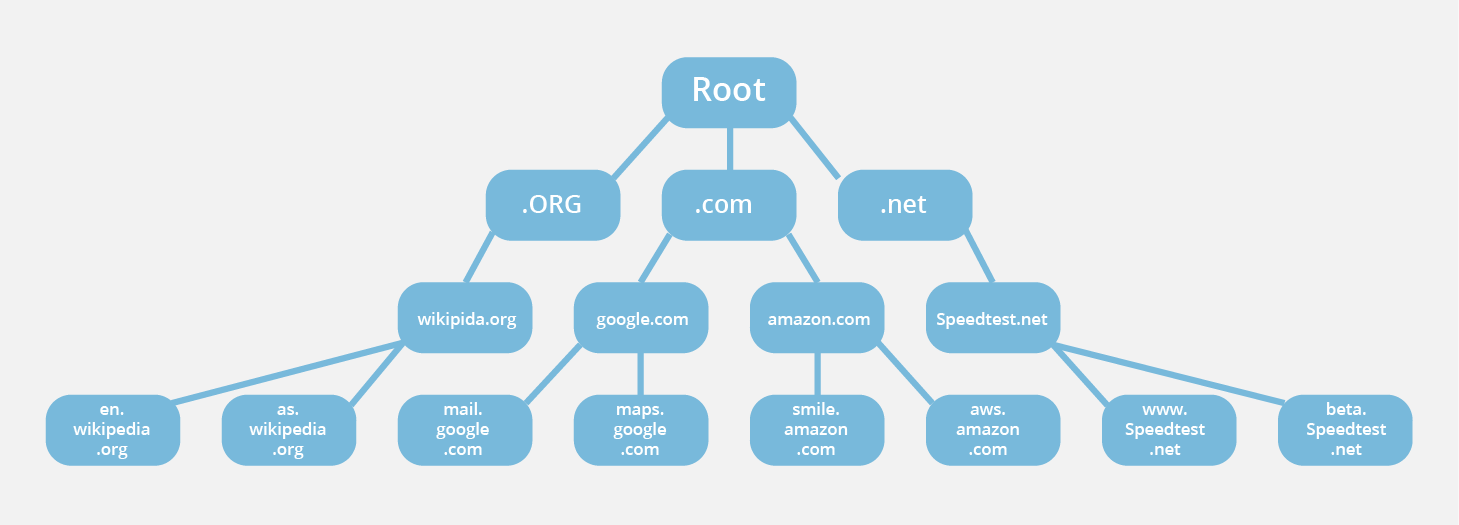

Root Name Servers

Root servers are DNS nameservers that operate in the root zone.

These servers can directly answer queries for records stored or cached within the root zone and refer other requests to the appropriate Top Level Domain (TLD) server.

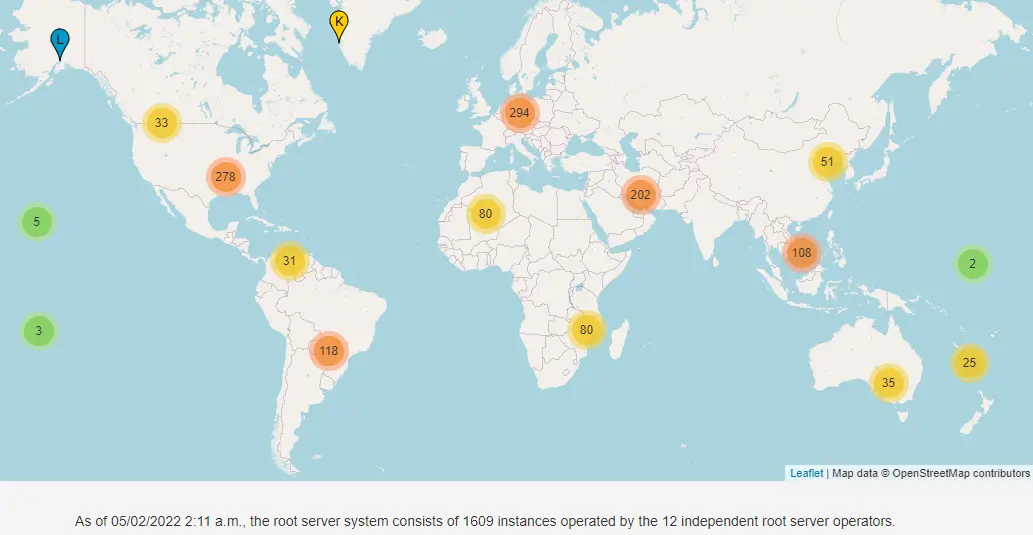

Only 13 root server IP addresses keep the internet traffic flowing, maintained by 12 independent organisations.

There are over 1,600 instances of these 13 root server IP addresses to handle all the internet traffic at any time.

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) operates servers for one of the 13 IP addresses.

Verisign is the only organisation that directly operates two root server IP addresses.

You can see more details of the root servers and their operators at https://root-servers.org/.

Authoritative Name Servers

The authoritative DNS server is the final holder of the IP address of the domain your computer is requesting.

It’s the final DNS result sent back to the initial requester.

Suppose your ISP’s recursive name server finds that the records sent back for an IP address are outdated. In that case, it will eventually ask an authoritative name server for the actual IP address.

An authoritative server is likely to be a server at the ISP where you registered and currently maintain your domain name’s DNS records.

The Complete 8-Step DNS Lookup Process

- A user types ‘example.com’ into a web browser, and the query travels into the Internet and is received by a DNS recursive resolver.

- The resolver then queries a DNS root nameserver.

- The root server then responds to the resolver with the address of a Top-Level Domain (TLD) DNS server (such as .com or .net), which stores the information for its domains. When searching for example.com, our request is pointed toward the .com TLD.

- The resolver then requests the .com TLD.

- The TLD server then responds with the IP address of the domain’s nameserver, example.com.

- Lastly, the recursive resolver sends a query to the domain’s nameserver.

- The IP address, for example.com, is then returned to the resolver from the nameserver.

- The DNS resolver responds to the web browser with the domain’s IP address initially requested.

Once the eight steps of the DNS lookup have returned the IP address, for example.com, the browser can request the web page:

- The browser makes an HTTP request to the IP address.

- The server at that IP returns the webpage to be rendered in the browser (step 10).

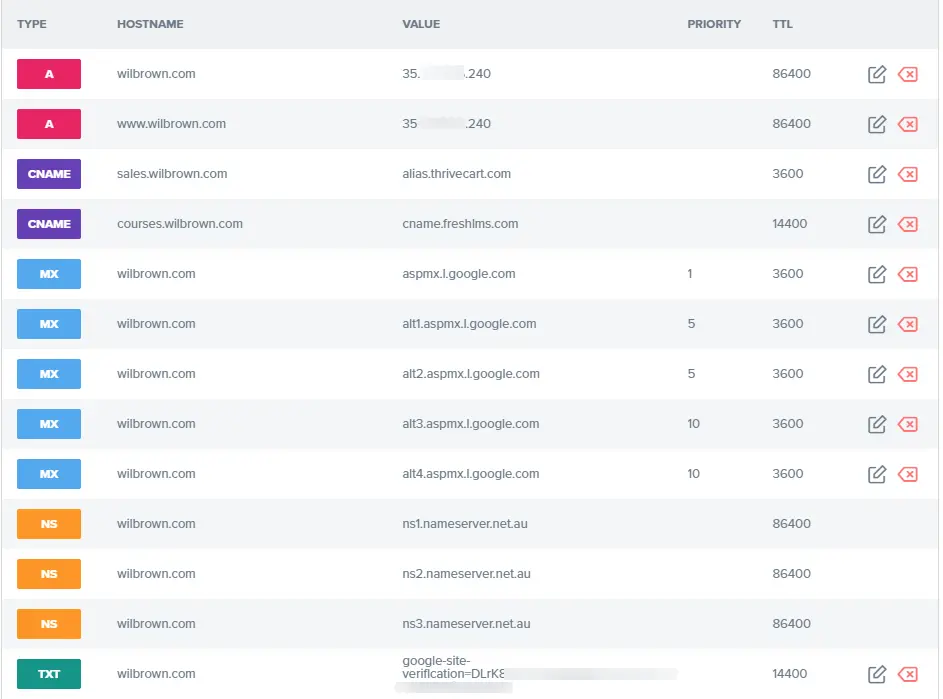

What Are DNS Records?

Each domain name can have a lot of different bits of data associated with it that provide information about a domain, including what IP addresses are associated with the domain and how to handle requests for other mappings.

These records consist of a series of text files written in what is known as DNS syntax.

In the previous example, we looked at IP addresses mapping to a domain name.

This is just one type of DNS record called an A record. There are many more.

Here are the most common DNS records that you are likely to use.

- A record – The record that holds the IP address of a domain. This is the IPv4 address used for mapping your domain name to a web server.

- AAAA record – The record that contains the IPv6 address for a domain.

- CNAME record – Forwards one domain or subdomain to another does NOT provide an IP address. You may use this if you’re mapping services such as an LMS (Learning Management System) to a subdomain of your domain. For example, I have courses.wilbrown.com mapped to my FreshLearn LMS account.

- MX record – Directs mail to an email server.

- TXT record – Lets an admin store text notes in the record. These records are often used for domain and email security. For example, Google Analytics may ask you to add a TXT record to prove that you own the domain.

- NS record – Stores the name server for a DNS entry.

There are more DNS records – see Cloudflare’s extensive description here https://www.cloudflare.com/en-au/learning/dns/dns-records/.

Here’s a screenshot of my wilbrown.com DNS records.

Wil’s Top 3 Domain Name Tips

Tip 1: Register a Domain Name Using a Generic Admin Email Address

When registering a domain name, update the administrative email address with a generic address such as [email protected] or hello@, or support@.

Domain registrars will only send domain name renewal notifications to the administrative email address stored in the domain name record.

If marketing director “Kevin” registered the company domain using his [email protected] email address and then left the company, those email renewals would bounce, resulting in a company losing that domain name.

Tip 2: Shorter Domain Names Are Generally Better

When it comes to domain names, the golden rule is that shorter ones are generally better than longer ones, but try to avoid a collection of letters unless your brand is already established.

So, for example, imagine a fictitious company called “Xavier’s All Year Zorbing” are looking for a domain name.

Example:

- xayz.com – short and somewhat memorable but useless if people don’t associate XAYZ with their current brand.

- xaviersallyearzorbing.com – too long and confusing to the eye. I see the work “Sally” in the middle.

- xavierszorbing.com – short and to the point.

Here are some reasons why shorter domain names are better than longer domain names:

- Easier to include on business cards and other printed promotional materials

- Easier to read

- Easier to remember

- More accessible to type on mobile devices

PS: Keywords in domain names do not affect Google SEO results – they are helpful for us humans only.

Tip 3: The “Over The Phone” Domain Name Test

If you are considering registering a domain name for your business, make sure it passes the “over the phone” test before you commit to buying.

It’s simple to do.

Call a friend and tell them to write down what you say next, then say your proposed domain name in a regular conversational tone.

If your friend asks you any questions regarding the spelling or pronunciation, you may want to rethink the domain name.

My first couple of business domain name choices were a disaster. I would have to spell them out letter by letter over the phone.

You probably want to avoid that hassle.

Common Questions

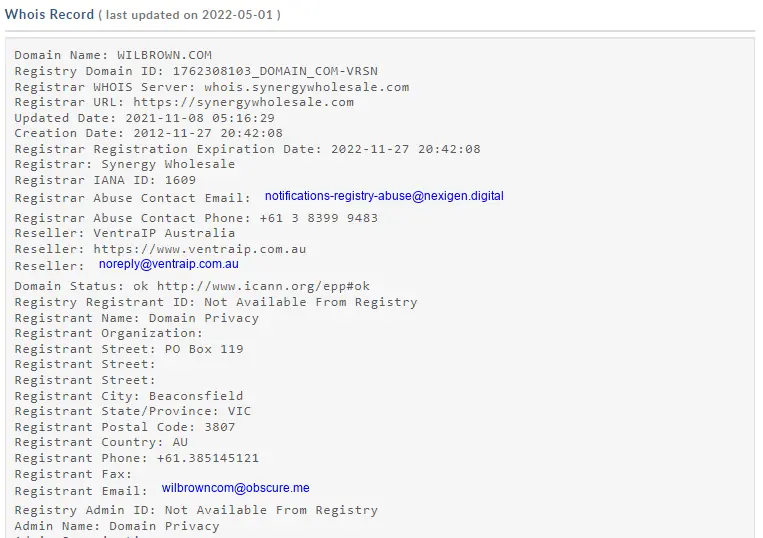

How can I find my domain name registrar?

Some domain owners may forget which organisation (registrar) they bought their domain from, or the information wasn’t recorded.

Whatever the reason, you can try and find out domain information from three sources:

- ICANN lookup: https://lookup.icann.org/en/lookup

- WhoIS: https://who.is/

- WhoIS Domain Tools: https://whois.domaintools.com/

The registrant may have domain privacy turned on, so you may not be able to get any company or registrant information, but there should be some clues in there for you to hunt down the registrar.

Here’s the WhoIs information for wilbrown.com.

You can see that I have domain privacy enabled, which obscures my personal information; however, the abusive contact email is set to Nexigen Digital, and the reseller is VentraIP.

That’s enough information to send an enquiry to both companies trying to hunt down the domain name.

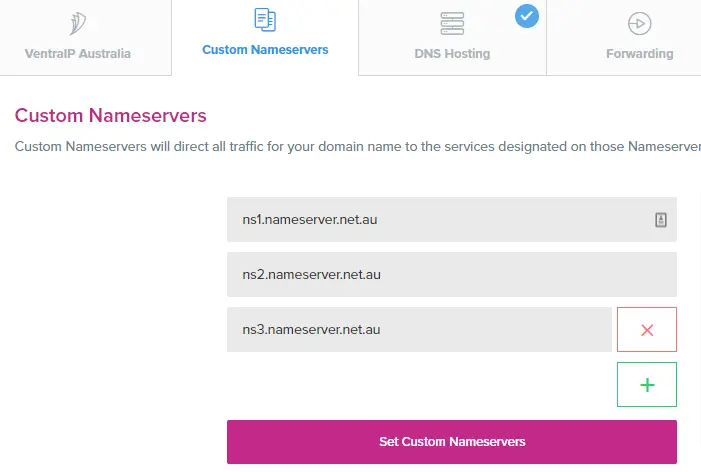

How can I update my domain’s name servers?

Once you have access to your domain registrar, you will be able to edit your domain’s DNS records.

Every company has a slightly different interface, but it’s usually just a simple form field editor.

Name servers are usually updated differently from the other DNS records because they are pretty important!

The image above shows the nameservers editor for my wilbrown.com domain.

How do I point my domain name to another ISP’s web server?

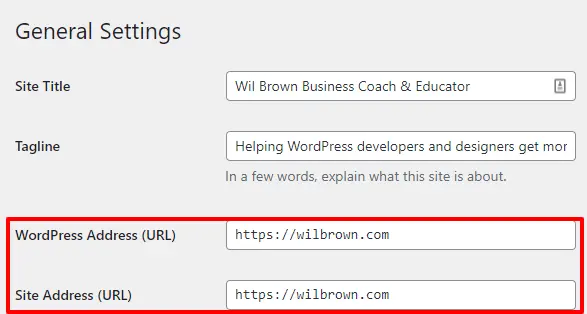

If you move your WordPress website to another ISP, you must change your DNS A and AAAA records to point to the new web server IP address.

The image above shows the edit field for the A records that maps www.wilbrown.com to the IP address of the webserver.

Every DNS record has a TTL value (Time To Live).

TTL is measured in seconds and tells the name servers when the DNS record information expires, after which new data is obtained from an authoritative server.

It’s probably a good idea to lower that number if you want a faster update to a new webserver.

Once the update completes, change the TTL back to its original value.

In this example, the A record has a TTL of 86400 seconds, equating to one day.

Do I need to use www for my website domain name?

No, that is your choice.

You can use www, which stands for World Wide Web, or ditch it and use the naked domain.

I prefer to use naked domains.

You should choose one method and stick with it, making sure you map one to the other using .htaccess or other server redirection methods.

URLs are unique, so Google Analytics and other web services will record www. And non-www visits as separate data streams.

You may lose half of your visitor data if you don’t redirect one to the other.

Remember to update the WordPress Settings> General URL fields to the correct domain name mapping.

Summary

DNS is a complicated system, but understanding the basics will help you handle client website launches and migrations better.

Do you still have questions about DNS Records?

Ask in the comments below.

#WPQuickies

Join me every Thursday at 1 pm Sydney time for some more WPQuickies – WordPress tips and tricks in thirty minutes or less.

Broadcasting live on YouTube and Facebook.

Suggest a #WPQuickies Topic

If you have a WordPress topic you’d like to see explained in 30 mins or under, fill out the form below.

https://forms.gle/mMWCNd3L2cyDFBA57

Watch Previous WPQuickies

-

How To Reduce TTFB and Improve Page Load Speed

-

Get Data From Multiple Tables Using SQL

-

How To Move WordPress To Another Web Host – WPQuickies

-

Who Owns WordPress? – WPQuickies

-

Will Page Builders Replace Web Designers & Developers? – WPQuickies

-

WordPress Updates: How Do They Work? – WPQuickies

-

Remove WordPress Header and Footer Using CSS – WPQuickies

-

WordPress Slugs What Are They & How To Change Them – WPQuickies